With the development of economy and progress of industrialization, more and more machine-made cloth has been taking the place of calico, home-made and hand-imprinted and dyed in the country. Therefore, blue calico, as a work of folk art, has been gradually losing its practical value.

Indigo Textiles: Technique and History, Gosta Sandberg

What do you see in this photo? Japanese yukata (cotton summer kimono) hanging on a line perhaps? It wouldn’t be an unreasonable guess based on the color and pattern, especially if you were just looking at the rolls of yukata fabric in Amy Katoh’s Blue & White store, like I was the other day. Hand-dying is a dying art everywhere, and we are lucky when people like Amy step up to help keep it alive.

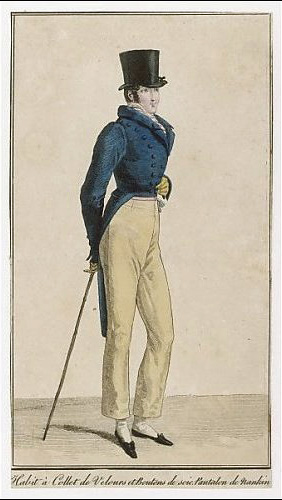

But the answer to my question above is actually not Japanese at all – it is Chinese nankeen, stencilled and dyed in an indigo bath. Originally, the word nankeen was used to indicate the very dense and unrefined hand-woven cotton fabric itself, but over time has come to be used interchangeably with its patterned and colored counterpart. Often referred to as blue calico, it was the main component of peasant clothing in China for centuries and in its plain form came to be an important export. A staple of British clothing from the late 18th century onwards, any Jane Austen fans among my readers will recognize it as a common fabric used for half boots worn for walking, as well as for mens breeches and pantaloons – the modern-day equivalent of chinos. Even its signature pale yellow color is often mentioned.

Ironically, while the upper classes in Europe were wearing nankeen, in China it was the fabric of the rice farmers, who used it for warm padded winter clothing. In Indigo Textiles: Technique and History, Gosta Sandberg writes “The jacket of the Chinese rice-farmer has been coloured with indigo since time immemorial. The reason for this is said to be that cloth dyed with indigo is many times stronger than undyed cloth and that it keeps insects and snakes at a distance, which is a considerable advantage for those working in open fields.” I don’t know if that is actually true, but it is consistent with work clothes in many cultures around the world, including our very own Levi’s.

Enter into our story – and there is nothing I like better than a good old-fashioned expat tale – Claire Russo and Liza Serratore, the founders and designers of LuRu Home, a new-ish textile based home design company working with modern versions of nankeen, based out of Shanghai. Selling pillows, napkins, place mats, tea towels and bags, all made from the custom hand dyed fabric in their versions of traditional Chinese patterns, it is good to see others taking up the banner of preservation, while innovating at the same time.

Liza and Claire had been friends since high school and kept in touch, planning to go abroad for work in response to the poor economy in the United States. After a few twists and turns, both ended up in Shanghai. One day they came across bits of old blue and white Chinese fabrics that they found in a tiny shop at end of long alley way – one of those magical moments that if we are lucky, we stumble across a version of, sometime in our own lives. The store was jam-packed with textiles, many sun bleached around the edges, and they came home with a few individual meters, recent but vintage. Their original impetus was to make things for their own apartment, and then for gifts, and from there the demand began to grow. They found they had passion for the fabric and as they investigated the printing process, a desire to rejuvenate the industry and bring patronage back to the artist.

The technique for making nankeen is a rice paste stencil resist technique almost identical to that of Japanese katazome. Just like the two countries currently arguing over the Senkaku Islands, they also argue over whose technique it was first. Frankly, I think it truly originates elsewhere in Asia, but I am not about to enter the scrum.

Does it look familiar? Antique Japanese katazome.

Both techniques use a paste glue to cover the open patterned area of a stencil, keeping it from absorbing the dye. In Japanese these stencils are called katagami – and I have written about them as decorative devices as well as a functional ones before. The Chinese nankeen artists do all their screen cutting by hand using simple craft paper that has been oiled. I can’t help but hear their Japanese counterparts whispering in my ear “They just use plain craft paper?” and the Chinese reply being “Why do they bother glueing all those layers of washi paper together with persimmon extract? Boy, that is a laborious waste of time!” While the Japanese use rice paste, the Chinese use soybean and lime paste mixed with water.

The base cotton is no longer hand loomed, but it is still very size limited based on the traditionally sized dying vats. It is also quite difficult to work with screens beyond a certain length so the largest screen possible is 32 inches and the rolls of fabric are 12 meters long. This automatically insures that all LuRu Home’s pieces are small batch made and variations are part and parcel of the product, depending upon the whims of the dyer and even the weather for drying.

The fabric is finished by using frosting-style knives to scrape away the paste after printing and then the fabric is put through a wash cycle with no soap and dried.

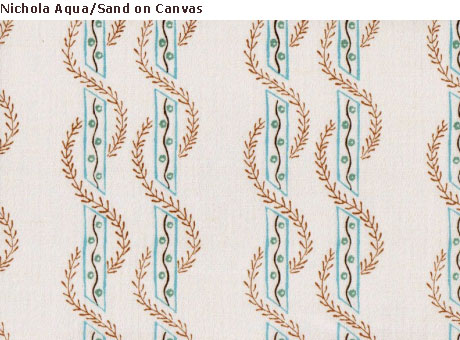

Their patterns have been inspired by historical patterns in An Overall Collection of China Blue Calico Vein Patterns compiled by Wu Yuan Xi, although not everything in the book is a traditional pattern (zebra anyone?). While Claire and Liza want to starting designing their own prints, the nankeen artisans will have none of it until the women build up more guanxi (relationship currency).

They have been extrapolating and changing the old prints and ironically that has helped them build guanxi as it shows their respect and appreciation for the process. A perfect example is the Flower pattern, which was too small and tight as it appeared originally. They enlarged the size and added white space to up its graphic punch. So for now, they are going to continue playing with tradition and plan to introduce a new pattern every season, which is twice a year, by adding one and pulling one, keeping 6-7 prints available at all times.

Their gorgeous website shows all their products and they also have a lovely lookbook with great styled shots. This outdoor view, also shown above previously, is my favorite.

I’m dying for a few of the adorable tea towels, pun untended! They make great gifts too.

So now for the fun part! Liza ad Claire have generously offered one 13 x 22 lumbar pillow (insert included!) in one of their four most popular patterns On The Fence, Babyteeth, Dot Dot Dot and Flower – the giveaway winner’s choice. All you need to do to enter the giveaway is leave a comment below. If you like LuRu Home on Facebook, I will enter you in the giveaway a second time, doubling your chance to win. They can ship to the winner anywhere in the world as they have stock in both the USA and China. The giveaway closes Monday night at 12 EST. I am crushed, of course, that I can’t enter myself!

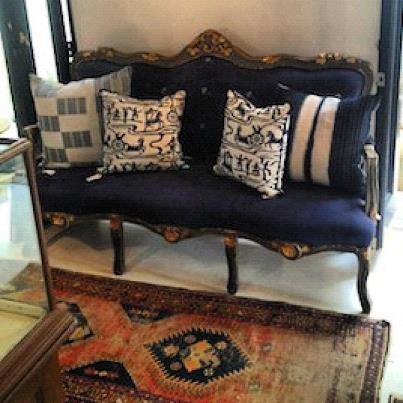

Their pillows look great styled with other indigo and blues, as seen here at Nicky Kehoe…

…as well as with an assortment of other colors, like here at Black & Spiro.

Although record prices are being set for fine antique at auctions by wealthy Chinese looking to repatriate lost treasures, the locals LuRu works with are a bit bewildered by the women’s’ fascination with nankeen. Anything folk art based is undesirable these days in China. Louis Vuitton or (even Luois Vitton) is what is hot. But Claire and Liza have stiff competition from other buyers in procuring their fabric. From whom, you may ask? Can you guess?

The Japanese!

Image credits: All images credited to LuRu Home or the publications listed with the exception of #2 (me) and the 19th century fashion plates from Lady’s Repository Museum.