prov-e-nance ˈpräv-nən(t)s, ˈprä-və-ˌnän(t)s

noun. the place of origin or earliest known history of something.

In my first Provenance column since my move, I am turning my attention to the art of inlay, which seems extremely apropos as it is one of the high arts of the Islamic world. I was also lucky enough to spend some serious time this past summer with the extraordinary collection of inlaid furniture and objects found at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. Even the best photos can only do this kind of detail so much justice and I will confirm for you that the 16th century Italian trestle table made of walnut with boxwood, rosewood and bone inlay shown above in the banner, was even more spectacular in person. That said, this is the kind of post in which all the photos are meant to be clicked on so that the detail can truly be appreciated.

The desire for ornamentation is universal and in the case of inlaid furniture, has transcended both time and geography. From the earliest known Mesopotamian example to those from ancient China, Egypt and the Roman Empire, artisans employed the technique of hollowing out cavities on the surface of an object and filling it with a different material – the inlay – to create contrast and pattern. Wood is most often the base material used for furniture, with other woods, ebony, ivory, bone, horn, tortoiseshell, mother-of-pearl and other shells being used for the inlay. Over the centuries the basic techniques have stayed the same, although the tools used have progressed hand in hand with technology, from early simple carving sticks to modern-day computerized cutting. More recently inlay materials have expanded to include the man-made, such as resin and other composites.

Inlaid furniture also tells the story of cross cultural influences and trade across borders. Inlay techniques were already perfected in North Africa before they were introduced by the Moors into Europe through southern Italy and Spain. Italian Renaissance artists carried the techniques further with their incredible detail and precision as the technique spread from northern Italy into Germany and then on to London via Flemish craftsmen in the later 16th century. It’s fascinating to compare the detail on this early 14th century Mamluk door from Cairo, inlaid with ivory, ebony and other woods, with this Venetian coffer made around 1520, also inlaid with the same materials. While the style of the inlay on the Italian piece is Islamic, the overall shape of the chest is most definitely Western European. This is not so surprising as strong trading links between Europe, the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East were already in place.

For the purposes of this post, I am going to neglect the development of similar indigenous European techniques such as marquetry and parquetry, in which pieces of wood veneer are applied to furniture (not inlaid) for decoration and pietre dure/pietra dura, in which semi precious and other colored stones are inlaid into marble. Equally compelling, they perhaps deserve a post of their very own.

As European exploration and colonization of India, the Middle East and Asia expanded, the Portuguese, Dutch and later English traders and then settlers arrived with a need for furniture and other objects such as sewing boxes and lap desks as there was little domestic furniture available. They had their European furniture and other imported pieces copied in native woods and then ornamented with traditional inlay techniques. Over time bustling export trade markets developed. Nowhere was the fusing of practical European pieces with local design more successful than in India and the Anglo-Indian furniture style – often referred to as British Colonial – was born. Bone inlay, as an alternative to the rarer and more valuable ivory and ebony, became the inlay material of choice because it was plentiful and readily available. Examples include this late nineteenth century colonial teak dresser inlaid with bone after it was made and what became an almost ubiquitous piece of colonial life, the planter’s chair. Both are highly collectible, extremely decorative and would look very at home in any global eclectic interior.

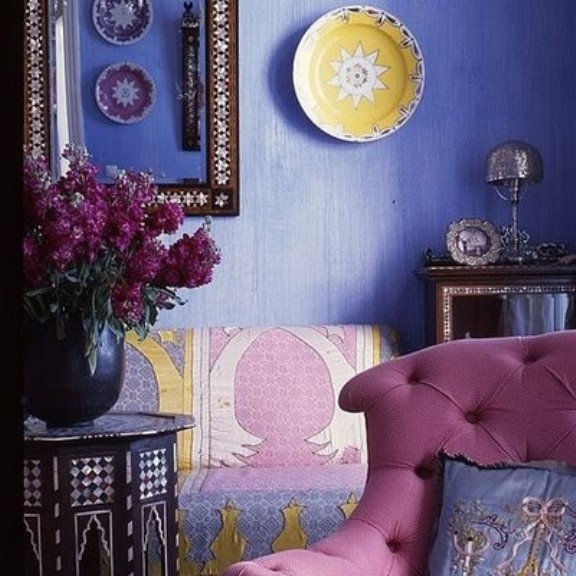

In North Africa and the Middle East local pieces such as dowry trunks and small tables were purchased and added to western style interiors, this being particularly popular in the latter half of the 19th century when exoticism became the rage during the Aesthetic movement.

They have cycled around to being incredibly popular again in today’s interiors and it is rare to find an interior photo spread these days that doesn’t include at least one octagonal Syrian or Egyptian table in this style. I could choose from hundreds of photos, but I love the unexpected combination and color play in this Tom Scheerer interior. The table is tucked in the corner and it demonstrates its versatility well in this unusual mix.

And let us be sure not to neglect Eastern Asia, where the art of inlay had been flourishing since before the 8th century. In Japan, mother-of-pearl was the most popular material, in addition to mixed metals and other techniques on lacquer pieces. While Japan’s production was domestically focused, the Portuguese began commissioning local workers to produce objects designed to appeal to the European market, like this tankard, in the latter half of the 16th century. Again we see a traditional western shape decorated in the local style. By 1635 the Portuguese were expelled and Japan remained closed to foreign influence for 250 years. Once reopened, design ideas from Europe were rapidly absorbed (as were design ideas from Japan in Europe). This elaborately inlaid curio cabinet or shodana, in the high Victorian/Aesthetic taste, was made for export in the late 1880s.

Elaborate inlaid cabinets were not limited to Japan and I cannot resist including these two absolute tour-de-force pieces that I was lucky enough to see at the V & A. The late 19th century Korean chest on chest used for storing clothes and bedding is decorated with phoenixes, cranes, peach trees and fish and utilizes stylized butterfly shaped metal fittings. The fully inlaid South American bureau is more of a mystery. It has been dated to around 1820, but little is known of it. It’s fascinating to see the European shape and techniques imported to the new world. More on each of these extraordinary pieces can be found here and here.

Inlay continued as a popular technique in the 20th century being perfectly suited to stylized designs appearing on Art Nouveau and Art Deco pieces. The modernist movement found a use for it as well, often simplifying from elaborate obvious pattern to accent and texture, best epitomized in these contemporary 1970s bone inlaid pieces by Karl Springer.

Interiors that feature inlaid pieces are irresistible – adding vibrancy with their mix of materials. Here are just a few examples from designers who are masters at using such pieces, including in clockwise order Anna Spiro, Katie Ridder, Amber Lewis, Schuyler Samperton and Ashley Whittaker.

Pieces from every era are pricy out in the marketplace. Well made new items are also expensive as even with advances in technology they continue to require a high level of craftsmanship. Bone and mother-of pearl are most commonly used on new inlaid furniture in the light of 20th century bans on the use or import of ivory and other precious commodities.

So where to find it? Antique pieces can be sourced from 1stdibs and auction houses, always a great place to look price wise if you know what you want. I’ve been quite lucky at flea markets and local shops, finding a small inlaid Indian table at a Japanese shrine sale, a colonial era set of tables at a run-down New Jersey antiques mall and most recently, an antique Syrian piece at a small shop here in Doha. Pretty global distribution if I do say so myself. Major online retailers like Wisteria, Serena & Lily and even Pottery Barn, as well as the drool-worthy UK-based Graham & Green carry the very figural mother-of-pearl and bone pieces we see a lot of these days, both in furniture and lovely accessories. Numerous online importers ship straight from India as well, although I don’t have any personal experience ordering from them.

The appeal of inlay is timeless as it adds a luminous and luxurious layer to any space and a whiff of exoticism and far off lands. On that note, the next few weeks will be devoted to the art of inlay here on Tokyo Jinja. From my own personal collection to contemporary interpretations of the craft, watch for numerous upcoming posts on the subject over the next few weeks.

In the meantime, if you would like to catch up on my previous Provenance posts you can find them over at Cloth & Kind as well as my related Provenance pieces here on Tokyo Jinja.

Victoria & Albert Museum, 2. My photo, Mamluk doors part of the The Museum of Islamic Arts collection, 3. Italian coffer from Victoria & Albert Museum, 4. Marquetry desk via 1stdibs, 5. Pietra dura via 1stdibs, 6. Chest photo via Wisteria, 7. Planters chairs via 1stdibs, 8.Table pair Christies, 9. Trunk Christies, 10. Syrian table close-up my own photo, 11. From Tom Scheerer Decorates by Mimi Reed, photographed by Francesco Lagnese, 12. Tankard Victoria & Albert Museum, 12. Shodana cabinet Bonhams, 13-14. Korean chest Victoria & Albert Museum, 15. Mother of Pearl chest Victoria & Albert, 16. Mother of Pearl detail close-up my photo, 17. Art deco desk 1stdib, 18. Karl Springer ottomans 1stdibs, 19. Anna Spiro in Absolutely Beautiful Things, 20. Katie Ridder in Elle Decor March 2008, photo credit: William Waldron, 21. Amber Interiors, 22. Schuyler Samperton, 23. Ashley Whittaker, 24-27. Tray and mirror via Wisteria, Commode and nightstand via Graham & Green, Bone inlay bathroom set via Pottery Barn,