Blanc de Chine wares have been produced for centuries in Dehua, a town in the coastal Chinese province of Fujian, since the Song dynasty (960-1279), reaching their peak production between the 16th and 19th centuries. Exported in great numbers throughout Asia, in particular to Japan before its trade restrictions in the 17th century, and later in mass quantity to Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, the pottery is best known for its depictions of Buddhist deities, which were used for home worship on family altars. The traditional Guanyin figurines – the Goddess of Mercy – so associated with blanc de Chine, are the same as the Japanese Kannon goddess, and often written in a variety of other ways such as Quan Yin, Kwan Yun, etc., in other cultures.

The look is so associated with Dehua kilns although porcelain of this variety was copied elsewhere, mainly in the nearby Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi province. The Dehua kilns were unusual in that there was a real division of labor as the items were made by mold, not on a potter’s wheel. Incised and applied decorations were added by the skilled artisans and the wares are fired at the highest possible temperatures. The clay itself is quite unusual, having very little iron oxide in it, which allows for the unusual pure color. But I think it is the shiny, almost wet looking glaze melded to the porcelain that makes it so appealing.

As I am always careful to warn people, there are serious problems with dating and attribution when it comes to Chinese porcelain – blanc de Chine is no exception – and even the experts can be fooled. Without a long history or provenance it is quite difficult to estimate when a piece was made, particularly as the same forms were produced for centuries. Also, much of the later white porcelain is not actually from Dehua and instead from Jingdezhen. Scholars argue all the time about color and translucence with the general feeling being that the older Dehua pieces have a more bone or ivory color and the Jingdezhen pieces are a true dead white. Yet I have seen pure white pieces at auction at reputable dealers labeled as Dehua blanc de Chine. Modern pieces are most distinctly that very pure white. Curieuse Chine keeps an incredible Pinterest page replete with many museum quality examples if you’d like to see more.

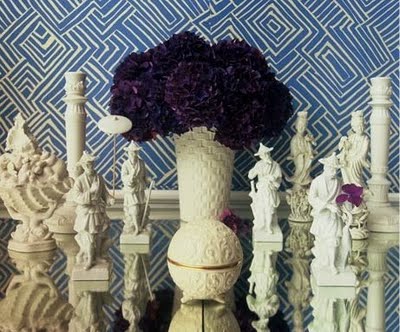

The modern design world has certainly taken note of blanc de Chine and designers such as Charlotte Moss, Mary McDonald,

Ruthie Sommers and others have used it to great decorative effect. Blogs such as Chinoiserie Chic and others feature it on a regular basis.

Often seen is this classic and formal way to display the white figurines on brackets or corbels.

It’s also quite common to turn the large statuettes into lamps which are extremely popular. I have a funny little caveat about these lamps found at the bottom of the post.

Blanc de Chine jumped back onto my radar when we visited Blenheim Palace, the home of the Dukes of Marlborough in England last month. There were fantastic Chinese porcelain collections – blue and white, famille rose – but I had never seen so much blanc de Chine and of such a variety and provenance in one place. The collection at Blenheim demonstrates the variety of objects made, which if you rule out all the different positions and details in the figurines, is actually not that great. The Dehua clay was not suited to making plates and large vases so smaller ornaments and the dense statues became their speciality. At Blenheim I saw foo dogs and other animals, libation cups in the shape of rhinoceros horn and a teapot with applied branches and flowers, small pierced cups and vessels and porcelain stands. This collection of about 40 pieces was supposedly given to the fourth Duke of Marlborough by a Mr. Spalding at the end of the eighteenth century at the height of the craze for all things Chinese. The impoverished eighth Duke (Winston Churchill’s uncle) auctioned most of the china from Blenheim at Christie’s in London in 1886 although the ninth Duke made the savvy choice of marrying heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt and later recovered and repurchased them and returned them to their rightful place.

Note the central teapot with its plum blossom motif which is actually very similar to the pieces in my own collection. I’m particularly enamoured of the items with the applied motifs and if you think about it, the plum blossoms have been rendered in a very Japanese style. Looking back, I wonder if that was what appealed to me about them even as I was living in China.

I wish I had better photos of my blanc de Chine to show you, but that will have to wait until I unpack the container next month. Most of my items are more workaday pieces, not the popular Buddhist figurines, much like this lidded jar.

So Blenheim put blanc de Chine back in my mind and then last weekend I had a fun yard sale find – a vintage blanc de chine lamp, ornately covered in flowers – for all of $5. (And I got the little plant stand for $2!) It’s not my usual taste and not very valuable, but I have a vision of it with a brightly colored lamp shade on a modern side table. Are you feeling it too?

I had this pair of antique blanc de Chine floral vases turned lamps that Courtney had featured in a post long ago in my inspiration files. They are long sold and out of budget anyway…

…but this one is currently available on 1stdibs from Prime Gallery for $1500. I’m feeling quite happy with my $5, although its going to cost more than that for sure to get it where I’m going. Hmm, I wonder if it can fit in my carry-on?

If you go out and google blanc de chine or read posts elsewhere, you’ll see one lamp style example over and over again that you have not seen here, with a pierced white body and stylized plum blossom motif.

They come in all shapes and sizes and some even light from the inside in addition to the bulb at the top.

Constantly referred to as blanc de Chine, these reticulated porcelain lamps are Japanese – not Chinese! Now that’s not to say that currently, China (and other places) aren’t turning out new ones, but originally these lamps were made in Japan, by companies like Seyei China. To be fair, they were modeled on some of the earlier imported Chinese wares. But the piercing approximates the “cracked ice” motif I often refer to, which is commonly paired with plum blossoms to signal the ending of winter. The early versions of the lamps stem from pre-WW II days, and by the post-war period they were being bought and brought home as souvenirs by soldiers and others stationed and/or visiting Japan by the thousands. In addition, there was a thriving manufacture and trade in the Guanyin figurine style lamps, so again, many of the lamps being sold as blanc de chine are in fact blanc de japon. To see more of this original Seyei sales brochure, click here.

This brings me to a pet peeve with the vocabulary of the design blog world. Its been bothering me for ages, so I might as well get my gripe out. The term “Chinoiserie” is so constantly misused for anything even vaguely Asian and it drives me a little batty. It’s not a catch-all phrase – it has a distinct meaning. For good measure, here is the Wikipedia definition:

Chinoiserie, a French term, signifying “Chinese-esque”, refers to a recurring theme in European artistic styles since the seventeenth century, which reflect Chinese artistic influences. It is characterized by the use of fanciful imagery of an imaginary China, by asymmetry in format and whimsical contrasts of scale, and by the attempts to imitate Chinese porcelain and the use of lacquerlike materials and decoration.

I don’t even love that definition, but it will do, the key phrase being “a recurring theme in European artistic styles.” Chinese antiques are not Chinoiserie! Yet everywhere I look actual Chinese antiques get called Chinoiserie, Japanese and Japonesque stuff (which are different from each other) is mislabeled as Chinoiserie, Japanned English furniture gets referred to as Chinoiserie – which is actually the right idea. A perfect example of modern Chinoiserie is this Elle Decor top 10 list, which is a grouping of contemporary furnishings inspired by Chinese design.

I think its important that as bloggers we use terms correctly, otherwise they lose their meaning as things are repeated, referenced and reposted. So arguably, real blanc de Chine is not Chinoiserie!

So now I’ve had my little rant on Chinoiserie, and I’ve written about Japonisme quite often, so it seems to me that come Doha, I’ll need to delve into Orientalism, another 19th century favorite of mine. We are at one week and counting down, on to our next adventure!