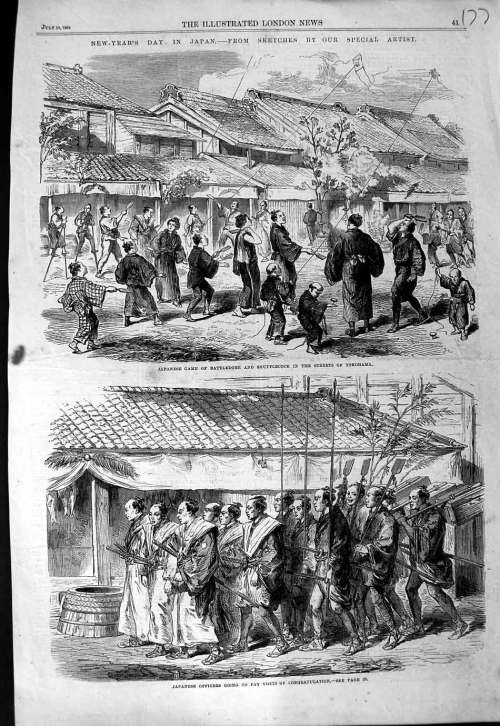

Art can tell us a particular cultural and historical tale. If you look up the origins of badminton, surprisingly enough, Wikipedia credits its founding to British Army officers stationed in mid 18th century India. Somehow they forget to mention its much earlier roots in similar games throughout Asia, such as a game called hanetsuki in Japan. If you click on the ukiyo-e print above, you’ll see that the characters are all holding a wooden paddle, called a hagoita, used to hit a shuttlecock in a game much like badminton, although without a net. Traditionally played by girls and women on New Years, the gaily decorated paddles are still sold today, and vintage and antique ones can be found by hunting around markets and shrine sales.

Because of their quick turnaround time, mass production and inexpensive prices, ukiyo-e prints depict just about anything and everything in Japanese society, hanetsuki not withstanding, and examples abound. I love the pale Edo period examples, such as this Utamaro print from 1804.

None of the women seem to be playing very actively.

Although, here she really does seem to be getting into her game.

Make sure to look at all the textile details on the kimono too.

A little photographic proof is nice. I love the way the photographer modeled this picture as if it was a print.

And a late 19th century page from The Illustrated London News has a joyful New Years Day in Yokohama full of hanetsuki and kite flying.

The later prints seem to depict children playing more often than women.

They are really sweet.

There has always been a great connection between kabuki actors and ukiyo-e, with many different artists depicting those characters and stories. I always imagine that the prints were the equivalent of modern posters of pop stars and the like.

Toyohara Kunichika literally got his start painting the designs for hagoita before going on to become a great Meiji period ukiyo-e artist. Born in 1835, he was demonstrating his artistic talents by the age of 10, working in a shop near his father’s bathhouse where he helped in the design of Japanese lampshades called andon (the same kind of lantern as shown here) and around the age of 12 he began more formal apprenticeship with Toyohara Chikanobu while at the same time designing actor portraits for actual battledores. As he started as a child, it is no wonder to me that his interest in this form never waned.

Rather than designing a scene in which people play hanetsuki like the prints above, these three prints of his depict kabuki actors actually within the frame of a hagoita and date from the 1880s.

These small koban (5 x 7) sized prints show his use of the bright aniline dyes imported into Japan from Germany in the 19th century. They feel almost garish to our modern eye, but the color red signified progress and enlightenment in Meiji Japan. Many thanks to Alex of Toshidama Gallery for sharing these images from an upcoming Kunichika exhibition.

Recently, at the newly re-opened Oedo Market at the International Forum, I have spotted some truly excellent hagoita. Its fun to compare them with the prints above.

It is rare that you see so many unusual old ones together. Prices were quite steep as a result.

And of course I can’t resist adding a modern decorative application. A friend has been collecting vintage hagoita for a wall display in her daughter’s room. You’ll notice she has stuck to sweet kewpie-pie girls – no scary kabuki actors found here – as it might very well give her nightmares.

What is it about decorative display with handles? It is always charming…see the fans and kashigata below.

Related Posts:

Hanga 101…a Quick Primer on Japanese Prints

Image credits: 1. via Ukiyoe-art, 2-5. collection of Museum of Fine Arts Boston, 6 & 9.via Floating Along, 7. The Illustrated London News, source unknown, 8. via Ronin Gallery, 10. via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 11-13. via Toshidama Gallery, 14-15. me, 16. L. Jardine, 17. via Little Emma English Home, 18. Amy Katoh Japan: The Art of Living, photo credit: Shin Kimura.